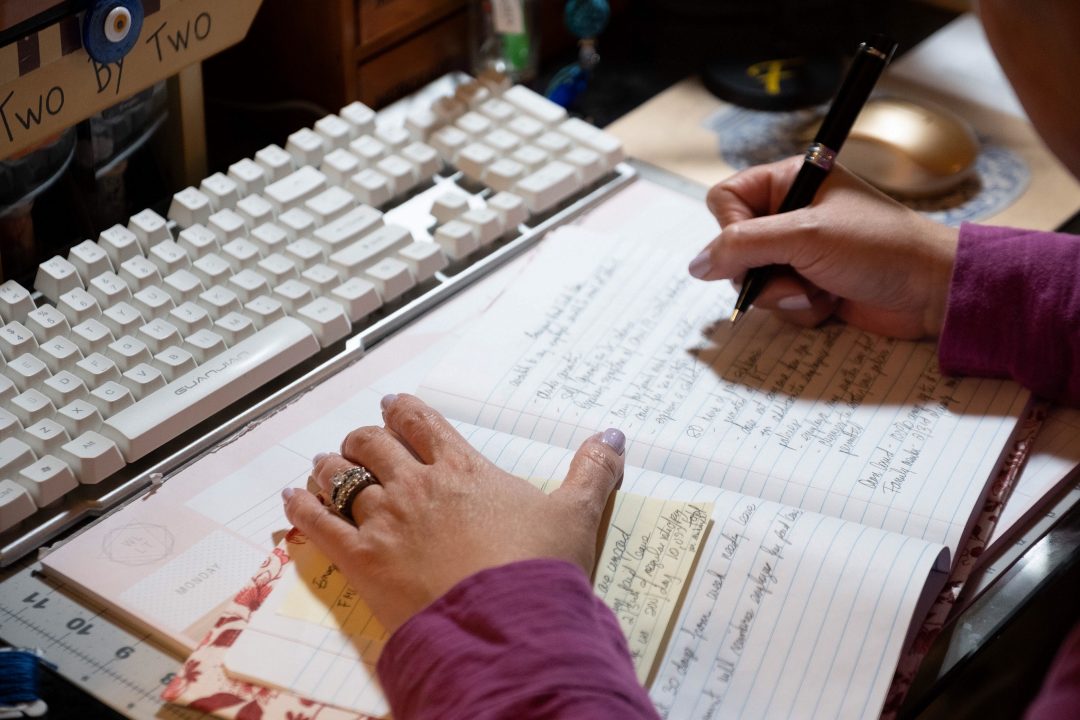

Just two days after students were forced to depart the University of Maryland, Baltimore County campus due to the impending COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Amy Froide took to myUMBC to post about historic journaling — “the more mundane, the better,” she wrote.

In her post, Froide, who is the chair of UMBC’s history department, encouraged students to keep journals to chronicle their experiences.

“If we don’t have accounts by individual, average people, the question is what then would people write the history of this event on?” Froide said, in a later interview.

Froide explained that a historical account based only on President Donald Trump’s press conferences or Maryland governor Larry Hogan’s press conferences or even an elementary teacher’s day-to-day life during public school closures would be incomplete.

“To build up a whole picture you need many perspectives,” Froide said.

The concept of historic journaling has existed for centuries. In fact, one of the earliest instances of European historic journaling, A Journal of the Plague Year, was written almost sixty years after the bubonic plague struck London. Writer Daniel Defoe amassed different contemporary accounts and research from those affected by the plague to finish the journal, and while not technically a firsthand account, Defoe’s journal is widely regarded as an accurate portrayal of life during the plague.

“There’s been an impetus to chronicle and write things down since the 1600s,” Froide said.

More recently, the mass observation experiment in the 1930s, 40s and 50s conducted by three former Cambridge University students aimed to record everyday life in Britain, and those findings helped shape British public policy.

Now, amidst the coronavirus pandemic, historians like Froide are urging others to begin writing the primary sources of the future.

Chronicling Coronavirus

For Conor Donnan, mass observation is about allowing those who are not typically viewed as the primary sources of history to have a voice.

Growing up in a poor neighborhood in Belfast, Ireland, Donnan was interested in why he could read books detailing Ireland’s history but could not get a sense of the lives of those who grew up like him.

As Donnan graduated from college and went on to complete his master’s degree at UMBC, he began to seek the intersection between academia and change-making and credits his time at UMBC as providing him with the means to connect the two.

“I’m a really big fan of dialogue, and I don’t think history is a research inquiry,” he said. “It’s a dialogue.”

Now a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, Donnan is hoping to encourage that dialogue with the help of fellow Ph.D. candidates Sarah Yu and Jennifer Yip Yuk Lum and their project Coronavirus Chronicles.

The publicly sourced database asks people from around the globe to submit diary entries about their experiences and feelings during the pandemic. The team is also collecting poetry, song lyrics, pictures and videos. Additionally, they plan to expand into the realm of TikTok, according to Donnan.

Donnan is hoping that Coronavirus Chronicles is able to reach people from marginalized backgrounds or communities, so that their voices can be elevated during and after this pandemic.

“What we find in history is that the voices of the majority of people are not observed, so you don’t really get the stories of the poorest of society, you don’t get the stories of women as much, transgender people, you don’t really hear stories from people of different races, different sexualities. What you see, in a historical sense, is that you miss things,” Donnan said.

Currently the database has received a couple hundred diary entries, but Donnan believes that by the end of the pandemic they will receive a couple thousand.

“As a society, we’re not one story,” he continued. “We’re a collection of different stories. It’s a tapestry.”

Collecting in Quarantine

For Allison Tolman, vice president of collections at the Maryland Historical Society, mass observation is about letting people know they are not alone.

The goal is to help people “feel seen,” Tolman said. “If we can do that, we feel like we’re helping our community.”

With the launch of a new initiative called “Collecting in Quarantine,” the historical society hopes to record stories from the homefront, but also from the business perspective in order to “collect the data in different ways,” Tolman said.

Maryland is, according to Tolman, a “good state” to be collecting experiences in, since it is so close to Washington, D.C. Additionally, the Maryland Historical Society has a rich history of documenting different kinds of phenomena through observation. It houses collections of letters from the Spanish flu of 1918 to the Annapolis yellow fever epidemics of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Tolman said that the historical society is trying to get participation from all across Maryland, so that they can “capture the different lives people are living right now,” she said.

These experiences will help future historians — and future generations — understand the nuances of life during the coronavirus pandemic.

One account that has been posted to the Maryland Historical Society’s blog details one woman’s experiences walking her dog while maintaining proper social distancing. Another finds a man at Safeway, staring down a freezer section full of shrimp from China in an otherwise depleted store.

These accounts, said Tolman, seem mundane to us now, but in one hundred years, they will provide context and a real world account of how government orders and anxiety affected us.

“We need to be thinking about who comes after us,” Tolman said.