Citizens’ recordings of the police beating and killing black men, women and children have been crucial in exposing the racist violence ingrained in police departments across the United States. People post these videos on social media, calling for action and fueling protest movements like those ignited by the killing of George Floyd by Minnesota police officers.

On-the-ground recordings and depiction of the protests become further evidence of police brutality as people upload videos of police shooting tear gas at distant protestors, police instigating violence and police SUVs driving into crowds of protestors. As major news media like CNN and FOX fail to contextualize and accurately depict the violence protesters face at the hands of police, people’s videos and live accounts become important in accurately documenting the protests. These are often picked up by local news media and help correct the narrative around protesters.

If you are one of these people tweeting, recording and distributing live information about the protests, you are participating in citizen journalism. Citizen journalism is reporting on news events by people who are not professional journalists, usually shared via social media.

This definition encompasses a lot of people posting right now, so it is important to know how to protect yourself and your rights.

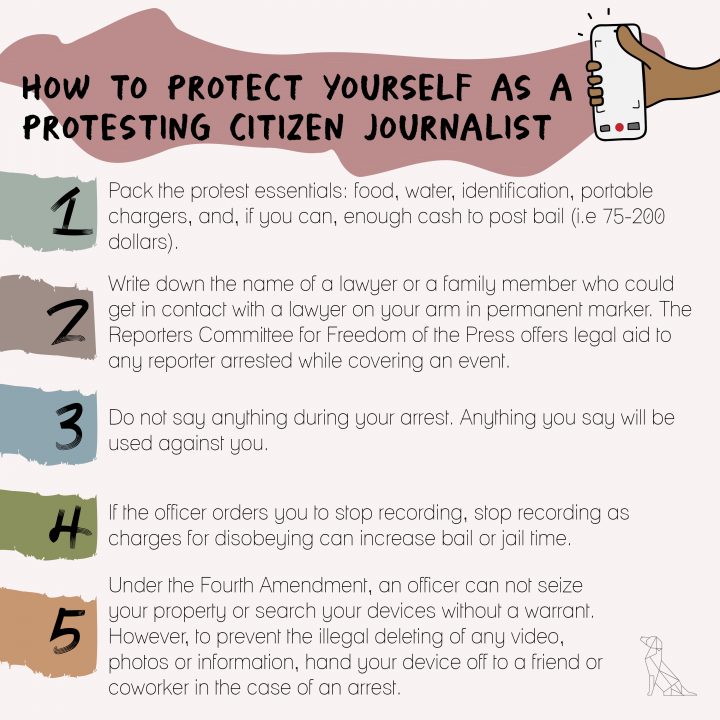

Pack your bag with the protest essentials: food, water, identification, portable chargers, and, if you can, enough cash to post bail. Bail varies person to person and crime to crime, but the National Press Photographers Association says people should carry between 75 and 200 dollars.

Travel in a group of friends, acquaintances or coworkers. If going to a protest alone, tell a friend or family member that, if you do not contact them by a certain time, they should assume you were arrested.

Whether traveling in a group or not, write down the name of a lawyer or a family member who can get in contact with a lawyer on your arm in permanent marker. This ensures that you have someone to call if you are arrested and the police confiscate your belongings. If you do not have a lawyer, The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press offers legal aid to any reporter arrested while covering an event.

If getting arrested, Rima Kikani, a lawyer with Rollins, Smalkin, Richards & Mackie L.L.C and professor at the University of Maryland, College Park, emphasized that anything you say during the arrest can and will be used against you. She specifically advised to not say anything once your arrest begins.

“Do not talk to anyone except your lawyer,” Kikani said. “You don’t know how those statements will be used against you or twisted.”

Videos of your arrest or the arrests of others are crucial in accurately depicting the police violence occurring at the protests. You, as both a citizen and a citizen journalist, have the “right to film government officials, including law enforcement officers, in the discharge of their duties” as stated in Glik v. Cunniffe.

However, Kikani says if you continue to record after an officer tells you to stop, you can have the additional charge of disobeying an officer brought against you even if the charge would not hold up in court. Dr. Eric Easton, a professor of law emeritus at the University of Baltimore School of Law, also counsels citizen journalists to follow any orders given by the police.

“A journalist receiving an order to cease and desist and move on, it may be prudent to comply with that order, whether it turns out to be a proper order or lawful order in the long run,” Easton said.

While Easton advises citizen journalists to obey officers, he does say that you can later question the police officer’s order and infringement on your First Amendment rights in court. This is particularly important as many members of the press have followed orders only to be pepper sprayed or detained.

If you do have video, photos or writing on your phone, camera or another device that you believe are important to your case or that could be used against the police, hand that device off to a trusted individual during the arrest. While it is illegal for police to seize, unlock and delete videos, photos and other content off a person’s device without a warrant, as stated by the Fourth Amendment, giving your device to someone prevents it from ever being held by police. Easton explains that newer technologies like the use of facial recognition to unlock phones have yet to be ruled as unlawful for police to use, so it is in your best interest to ensure your devices are not in the hands of police.

While these are all ways to protect yourself, it is important to note that there are no special legal protections for citizen journalists.

“When you’re actually out there on the streets protesting, you’re following the same laws as everyone else,” Kikani said.

In general, Easton advises citizen journalists to be careful and try to identify yourself as a member of the press, even if you do not have official credentials, as that might prevent your arrest.

“You don’t do any good as journalists when you’re taken out of the picture,” Easton said.