With the mass adoption of online learning in response to the novel coronavirus, it seems that we have entered the schooling of the future. So why is attendance still widely considered so necessary?

In this time of potentially indefinite online learning, mandatory synchronous classes are outdated and unhelpful, considering the pervasive climate of fear and economic, physical and mental health difficulties that students are facing.

This isn’t to say that synchronous lectures need to be abandoned entirely. Many people both benefit from and enjoy attending classes in real-time, and some courses simply make more sense to be held synchronously.

What needs to be abandoned, however, is the mandatory aspect of these synchronous classes. By doing away with attendance policies, classes can become both synchronous and asynchronous at the students’ discretion.

Our era of technology already allows students to view and interact with lectures, teachers and classmates almost entirely in their own timeframe. And what better time is there than college for engaging in a format so rooted in independence?

Many freshmen enter college right out of high school, and they are just beginning to come into their own as adults. Most universities seem to support this by trying to foster a culture of independence in their students. However, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County seems to be faltering in applying this to online classes, where attendance policies are only serving to hinder students’ ability to choose how they structure their lives and handle their workload.

Elizabeth Aguas, a junior biology major, stated that her synchronous Biology 142 course “requires you to be logged in for at least one hour to even count for attendance,” also noting that “[it] doesn’t matter if it was 59 minutes [or] you got kicked out, you were technically never there.”

This all-or-nothing approach to class attendance is detrimental not only to student motivation and stress levels, but also the often large percentage of a student’s overall grade that participation tends to make up. Participation can account for 10 percent of a student’s grade, meaning that it has the power to decide if a student will be getting an A or B in a class.

This also means that students who repeatedly experience technological difficulties such as spotty wifi and connectivity issues are automatically at a disadvantage. Students who ace every exam and have a strong understanding of the course material may not receive a grade that reflects their knowledge because of uncontrollable factors that affect participation — and no student should have their grade suffer because of an unfair predicament.

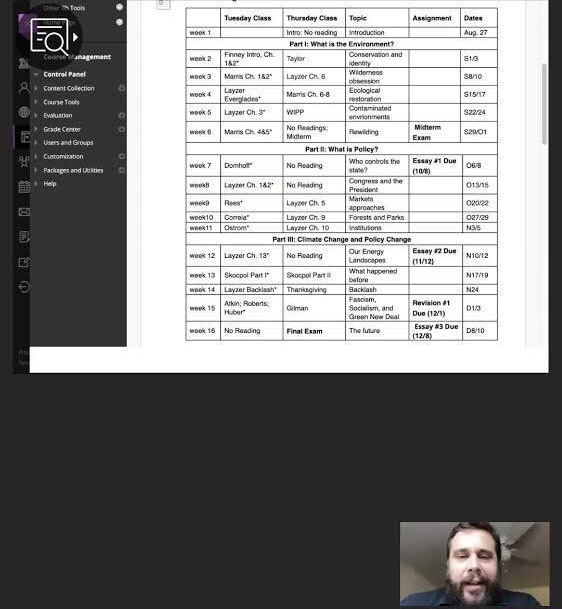

On top of this extremely strict attendance policy, Aguas explained that “exams are also at the lecture time, and [they] have to log in on to the [BlackBoard Collab] so that if there are any questions, the professors are there to answer them live.”

While it is certainly beneficial for students to have access to the live assistance they might need, it is absurd to require that students be present for said assistance on threat of receiving a zero for their exam.

Such forms of test-taking, much like their pre-pandemic counterparts, can initiate flare ups of anxiety or even panic attacks for some students, as well as make memory and performance difficult for those with disorders or disabilities such as ADHD.

Despite this, the rocky shift to online learning does not need to be riddled with fear and stress. Instead, it is an opportunity for our largely stagnant education system to push forward, and to use the current limitations to find ways to improve.

In order to embrace this, mandatory synchronous classes have to go.

While some classes such as labs, discussions and other similar formats — given the way they’re currently structured — would suffer or become impossible to complete without synchronous attendance, this is no cause for synchronous attendance to be mandatory for the majority of courses, especially when many instructors have begun to show that there are ways to adjust schooling to everyone’s needs.

Even typical test-taking, something notorious for requiring supervision, has found a clear alternative in many classes. The new norm, which I have already seen in several of my courses, appears to be one in which tests, quizzes and exams, while still timed, are available to start at any point during the testing day.

This approach still upholds the timed aspect of test-taking, which allows instructors to properly gauge their students’ overall learning, while still maintaining class structure. It also allows for students to dictate when in their schedule they will be most prepared and able to take an assessment.

So, whether we are presented with exams, labs or run-of-the-mill classes, we must let students exercise clear control over both their school lives and regular lives. After all, both students and staff deserve a helping hand right now.