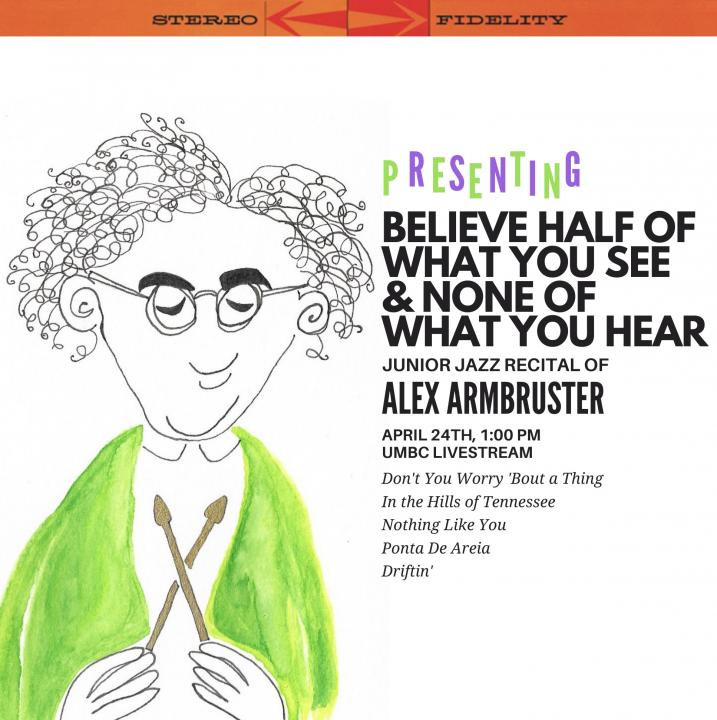

The invitation to see Alex Armbruster’s junior jazz recital, “Believe Half of What You See & None of What You Hear,” on behalf of the paper was one I grabbed without hesitation. On Saturday, Apr. 24, I did something I had not done in a very long time and got a glimpse into what the transition back to in-person performances and gatherings will feel like. Beyond excited to see live music, and happy to have an occasion I could dress up for, I made my way to the Performing Arts and Humanities Building that afternoon.

For over a year now, our lives have been placed on pause. It was strange at first, adjusting to isolation, to conversations over computers, to rethinking everything we once took part in so lightly. But we did it, we adjusted. As summer rolls around, excitement is building for the moment we are able to press play, to resume what we have been forced to put aside. While life has been slowly but surely starting to resume as planned, I could not help but wonder what is this “normal” we all keep mentioning, keep preparing ourselves for? Surely, nothing would feel the same as it did before.

Walking past the campus pond and up the long path of stairs, I came to realize that nothing about this outing felt normal. The 10-minute walk seemed like 30. Even something as simple as talking to strangers to ask for directions inside the building was a much harder task than I anticipated. The weirdest feeling of all was the one I had when I walked into the Earl and Darielle Linehan Concert Hall, fully realizing where I was and what I was there to do.

It was a beautiful room, not too large or intimidating like many of the stuffy concert halls I had been in before. It was incredibly open as well, even more so considering the number of guests had been significantly reduced for safety concerns. As 1:00 p.m. was nearing, I found a seat in the middle of the room, rows away from the nearest person, and felt a silence take over the hall. The only noise came from people shuffling in their seats and clearing throats, the crinkling of paper as they opened their brochures, and the mysterious movement happening behind the stage.

When the time came and the lights dimmed, eight musicians walked out for the first piece: Alex Armbruster, Bentley Corbett-Wilson, Tim Edwards, Riccardo Jefferson, Miles Malone, Kyra O’Donnell, Brandon Gouin and Russell Brown. They took their places, ready hands and mouths placed delicately on instruments, masks secured, and lifted their eyes to one another in communication.

All at once music filled the hall, a lively cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” immediately lifting the audience. The playfulness of the piece surprised me in the best of ways, each musician jumping off another, the intensity of the drums building in a fantastic solo by Armbruster towards the end.

The rest of the recital only built on the excitement of the first piece, each cover bringing with it some slightly different sound. Ira Schuster and Sam M. Lewis’s “In the Hills of Tennessee” introduced a softness and great piano, Bob Dorough and Fran Landesman’s “Nothing like You” was upbeat with animated singing, Milton Nascimento’s “Ponta De Areia” was accompanied by a mellow saxophone and the sounds of chimes and finally Herbie Hancock’s “Driftin” brought a perfectly crafted conclusion with percussion.

I’ve never been an expert on jazz music, but even with such little knowledge on the music itself, I found myself loving this recital and excited to reflect on it. As the concert came to an end, final bows and claps exchanged, I left the experience thinking not only about what I had just heard, but thinking heavily about what COVID-19 has meant for these musicians, and everyone in the arts community.

I had made a first step back to “normal” just as those eight musicians had. I realized that while I sat in the audience, aware of how confusing and surreal it was to be attending an event with people, I had not given much thought to how it must have felt for these musicians to play for an audience. We have all had to give up a lot to keep ourselves safe these past months, but not all of us have had to adjust in the same ways and sacrifice in the same ways as artists who perform and require a level of human inspiration.

The performance was eye-opening for many reasons, not only because the experience of hearing such amazing music was so special, but also because it showed me that students and staff must do more to support the University of Maryland, Baltimore County interdisciplinary arts community as we prepare for a far from “normal” Fall 2021 Semester.

In the wake of such devastating campus shutdowns that have hurt these students especially, staying involved with the arts, whether it be music, dance, visual arts or more, is absolutely vital to helping this campus return to what it once was and fostering connections between all students.