In art theory, there is the idea of aura — the concept that replications of a piece of art lack symbolic value that only the original can possess (think the canvas versus the postcard). I am not sure I believe in this idea, but I do think it has some merit, which makes me a bit sad. I know I will not be able to experience every great work of art in my lifetime, let alone see them in person. One of my 2020 New Year’s resolutions was to visit more museums. We all know how that went.

Nevertheless, being without museum access got me thinking about art that is best consumed from home — art that retains or, rather, transcends aura regardless of place. That is where “Everywhere at the End of Time” comes in. The album, created by Leyland Kirby under the moniker The Caretaker, depicts the experience of Dementia through music, and it is absolutely haunting.

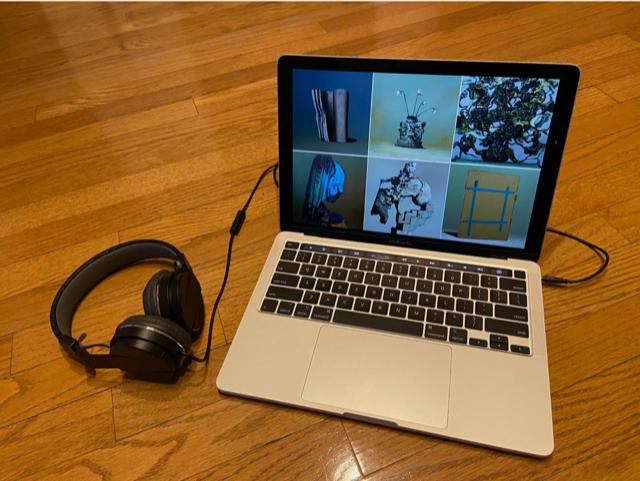

You might have heard of it on TikTok where memes revolving around the album’s six-and-a-half-hour runtime have grown popular, or maybe you saw its strange and unsettling album art while scrolling through your YouTube recommended page.

Listening to “Everywhere at the End of Time” is the most viscerally uncomfortable experience I have ever had with a piece of art. It is constructed to mess with your memory, replaying and distorting the same melodies over several hours until they are nearly unrecognizable. The album is divided into six stages that mimic the stages of Dementia, and each stage grows progressively more disturbing. What begins as an ambient ballroom record becomes a chilling noise and drone album that toys with your senses. It is confusing, upsetting and, most of all, moving.

“Everywhere at the End of Time” exists primarily in cyberspace. The album has over 7 million views on YouTube and boasts well over 100,000 comments. The community that thrives in this comment section is not something you will ever find when touring a museum. The museum experience is internal, private. Even when you go with a group, there is an expectation of quiet observance. Do not touch. Do not talk too loudly. Do not linger too long.

“Everywhere at the End of Time” is different; it begs you to engage, to cry, to rip out your earbuds and leave. It makes you a participant in the art, rather than the observer. Its digital medium offers listeners an opportunity to interact with other participants, and those interactions become part of the art experience.

In regular videos, the comment section is supplementary. Many people gloss over it entirely. However, when a video is six and a half hours long, a lot of people will, at some point, scroll through the comments. Then, when you add the heavy emotional weight of the video, it is almost inevitable that viewers will seek comfort in the comments. The comment section acts as the listeners’ companion as they slog through hours of exhausting sounds. Lighthearted jokes and encouragement from commenters keep listeners motivated to continue, and the heart-wrenching stories of commenters who have witnessed Dementia make the album that much more poignant.

Returning to the notion of aura, the value of a physical piece of art is often determined by its uniqueness. For example, there is only one Mona Lisa. Even if someone managed to paint an identical copy, it would not be da Vinci’s work, and therefore it would not be as valuable in the eyes of art buyers and sellers (who determine its market worth). The original is scarce but widely desired.

Walter Benjamin, the philosopher and critic behind the idea of aura, believed aura was detrimental to the experience of art. “The problem with aura is that you need to be an economic elite,” explained Craig Saper, professor and Interim Director of UMBC’s Language, Literacy and Culture Doctoral Program. “It’s very expensive. You have to buy stuff, you have to go to museums — that takes a certain kind of access — and Benjamin was against that.”

Because “Everywhere at the End of Time” exists in a virtual space, it has no physical form to which aura can be attached. Additionally, the album constantly changes as people engage with it, meaning that there is no single form that can be cited as its most authentic, original version.

And “Everywhere” is not alone. Over the last decade, music has become increasingly digital and, by extension, more accessible. YouTube is a virtual museum containing thousands of incredible works of art, all available for free to anyone with an internet connection. As the digital landscape evolves, artists find new ways to utilize its features to create unique artistic experiences — experiences that transcend aura.