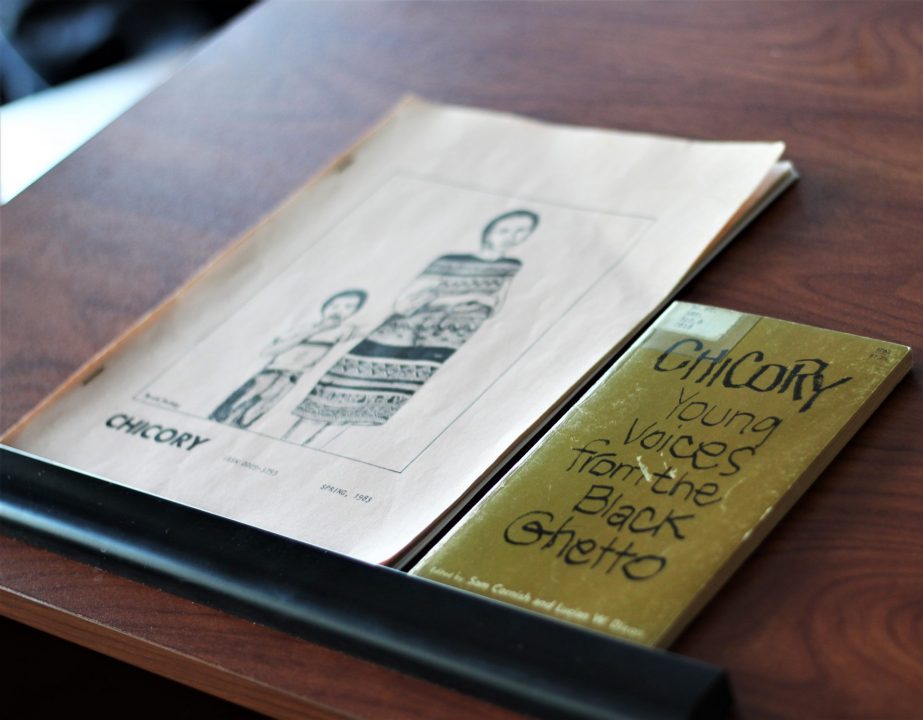

As part of the Dresher Center for the Humanities’ Inaugural Public Humanities Speaker Series, assistant professor of history and director of the Graduate Program in American Studies at Rutgers University, Mary Rizzo, delivered a fascinating lecture on the intersection of the Black experience and poetry within the historic Baltimore publication of “Chicory” magazine.

Her research centered around this magazine and how it is “the most authentic microphone of Black folks talking ever devised.” Upon coming across boxes upon boxes of “Chicory” editions hidden away, Rizzo and the Pratt Library in Baltimore breathed new life into the work by digitizing each and every page of every publication to be accessible on a public database.

In Nov. 1966, the first issue of “Chicory,” written by everyday residents of Baltimore City, was published. Publishing original poetry with little to no editing, the magazine grew as a space for young people of color in the poorest neighborhoods of the city to express themselves.

Working as a “vehicle for civic dialogue” and fostering a community environment among the Black ghetto, “Chicory” was for who Rizzo described as “people who don’t necessarily like to write, but who have something to say.”

These powerful, untouched words were profound in revealing the Black experience in Baltimore while also challenging the notion that poetry is meant only for the most elite and white writers in the literary world.

Rizzo explained, “The words of the people were already poetry.” This allowed submissions to be open-ended and unbound to any specific framework. One poem about the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination in her community was written by a twelve year old Black girl living in Baltimore.

Another powerful poem, “A Message From the Ghetto,” was written by two Black women and published in “Chicory” with their home addresses listed below for readers to contact, showcasing these women’s desire to continue the conversation of Black experience in Baltimore. This and other poems of “Chicory” highlighted the large part that everyday people played in organizing social change within the city.

Throughout the digitizing process, Rizzo and the Pratt Library came across challenges in determining who the legal owners of the poems were, given that the magazine stopped publishing in 1983 and many of the authors submitted poetry while they were very young, meaning they might not remember sending in their pieces.

Rizzo also faced challenges in dealing with the ethics of digitization and increasing the accessibility of the database itself. However, even though “Chicory” closed its doors to the publishing of poetic expression in 1983, the work of these young Black voices will continue to live on and inspire generations to come through this online database.

Follow Rizzo and the Pratt Library’s progress of digitization at collections.digitalmaryland.org and discover the profound, raw voices of the Black experience in Baltimore once again.