Kanye West, Lana Del Rey, Morgan Wallen — the list of ‘problematics’ seems ever-expanding. One has to wonder, at what point do you draw the line? When does an action become so unforgivable that you can no longer listen to their music? The issues with the artist vs. art spill over into literature too, with Harry Potter’s author J.K. Rowling revealing herself to be transphobic. Her statements horrified many HP fans and drove many members of the community to search for new ways to enjoy the fandom without endorsing Rowling. The big solution: “The Death of the Author.”

“The Death of the Author” was an essay published in 1967 by Roland Barthes, a French literary critic. The theory within the essay does not advocate literal death or killing; rather, “The Death of the Author” suggests that a piece of literature can and should exist separate from the author, that the author has no more power over the interpretation of a text than a reader.

What “The Death of the Author” does not propose, however, is the deplatforming of a creator. Those calling for the destruction of J.K. Rowling’s career and citing Barthes’s essay as their support — that is not how “The Death of the Author” works. This is an important distinction to make. No one should walk away from this article thinking that “The Death of the Author” is a justification for cancel culture. It is not.

Craig Saper, professor and Interim Director of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Language, Literacy and Culture Doctoral Program, explained that “The Death of the Author” can be applied beyond literature. “Art, music, media, even objects like plastic toys, or the ways that lovers talk to each other became topics for Roland Barthes and textual studies.” He continued, “It’s no longer about just literature or the canon, now we can use these theories to read everything around us.”

Along those lines, what happens when we apply “The Death of the Author” theory to music? Is it possible to interpret and enjoy music without taking the musician and the circumstances in which they live into account?

It is a difficult question. It may be possible to some extent, but, at some point, personality always leaks through. Even if you do not know anything about a person, the inferences you can make by listening to their music will affect your perception of them, and, by extension, their art.

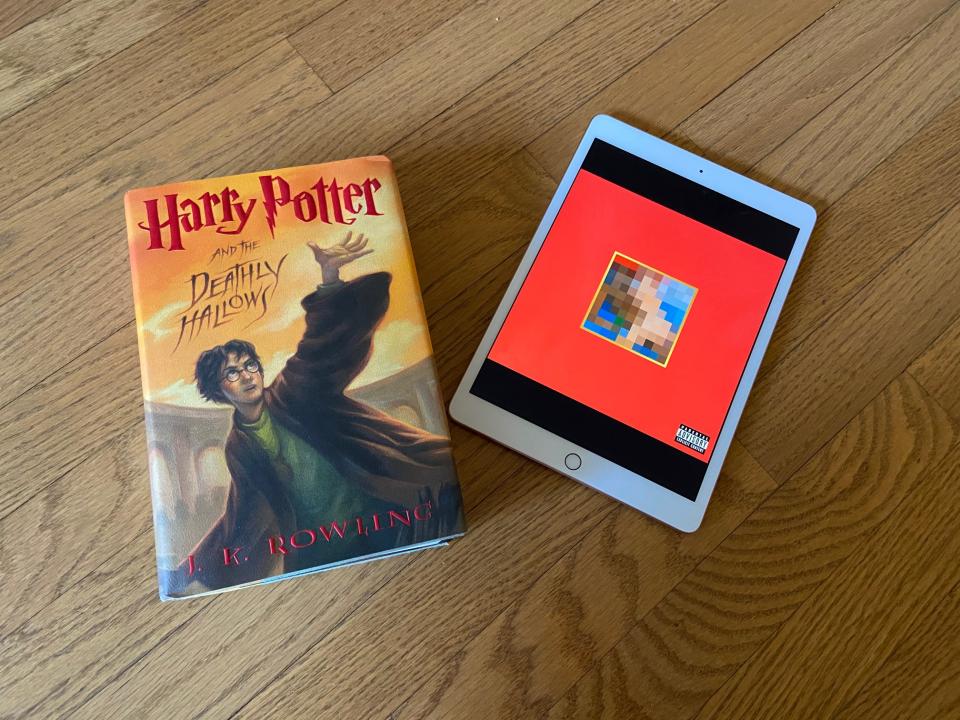

Take Kanye West for example: West is known for writing very personal music. “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,” West’s most widely acclaimed album, is filled to the brim with discussions of West’s relationships, flaws and experiences. Even if you did not know anything about West before listening, in the very first song of the album (“Dark Fantasy”), he talks about growing up Black in Chicago and touches on issues of racial injustice in America.

As you progress further in the album, more of West’s personality becomes clear: “I was never much of a romantic / I could never take the intimacy / and I know I did damage / ‘cause the look in your eyes is killing me” (from “Runaway”), and, later, “I’m lost in the world, been down my whole life / I’m new in the city, and I’m down for the night” (from “Lost in the World”).

Even without knowing about West’s struggles with mental health, his messy romantic pursuits and his inability to cope with fame/infamy, West’s vulnerability in verses like these envelop the listener in his personality. Listeners cannot help but empathize with West, and, therefore, West’s personality and background become a part of the music.

West is not alone in this: the creation of music is an intimate, vulnerable process. There is little separation between the musician and the music (especially for singer-songwriters, who have risen significantly in popularity in the last few decades). Additionally, there is an expectation for modern musicians to imbue their personality and their personal brand into their creations.

What if you do not like a musician’s personal brand, but you enjoy their music? Once again, Kanye West is a perfect example. Many of West’s fans dislike his political stances, and, with allegations of underpaying (or not paying at all) his performers at the Sunday Service Choir surfacing, a new wave of discomfort for West’s fanbase has emerged. But, undeniably, West makes incredible music. So what can “The Death of the Author” do to help?

Fans of West may not like the answer. Unfortunately, “The Death of the Author” does not absolve fans of responsibility for supporting West and other problematic creators. Modern musicians, even the controversial ones, still make money off of their music.

How, then, do fans cope with enjoying the works of musicians, authors, and other creators who say and do bad things? For this, “The Death of the Author” might have a solution. Barthes argues that a text is more than its author. According to Barthes, “a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination,” the destination being the consumer. Barthes urges readers to turn their focus away from the author’s intent and instead look closely at their own interpretation, what the text means to them.

We can do this with music, too. “The Death of the Author” would suggest that West’s controversial actions do not change the meaning of the words he writes. Further, their meaning isn’t decided by West, they are decided by the listeners. When I listen to “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,” I am not endorsing West himself; rather, I am resonating with the stories he tells. In my opinion, music cannot exist independent of its creators, but, if we employ “The Death of the Author,” it can be enjoyed despite them.